New study examining the increased mortality from night heat excess due to climate change

Excessively hot nights caused by climate change are predicted to increase the mortality rate around the world by up to 60% by the end of the century, according to a new international study that features research from the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health.

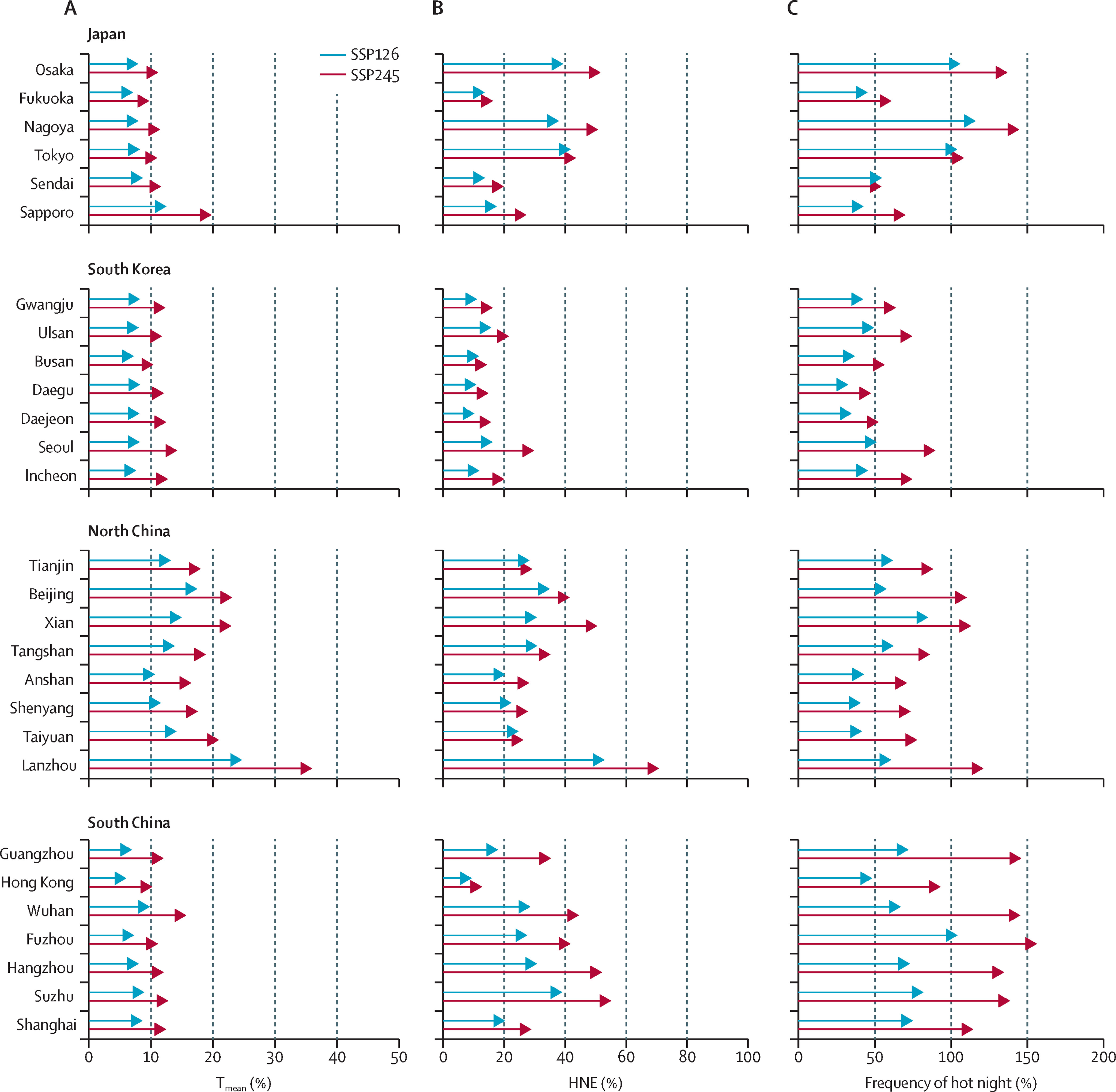

Ambient heat during the night may interrupt the normal physiology of sleep. Less sleep can then lead to immune system damage and a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic illnesses, inflammation and mental health conditions. Results show that the average intensity of hot night events will nearly double by 2090, from 20.4℃ (68.7℉) to 39.7℃ (103.5℉) across 28 cities from east Asia, increasing the burden of disease due to excessive heat that disrupts normal sleeping patterns.

This is the first study to estimate the impact of hotter nights on climate change-related mortality risk. The findings show that the burden of mortality could be significantly higher than estimated by average daily temperature increase, suggesting that warming from climate change could have a troubling impact, even under restrictions from the Paris Climate Agreement.

New publications on environmental justice from climate warming

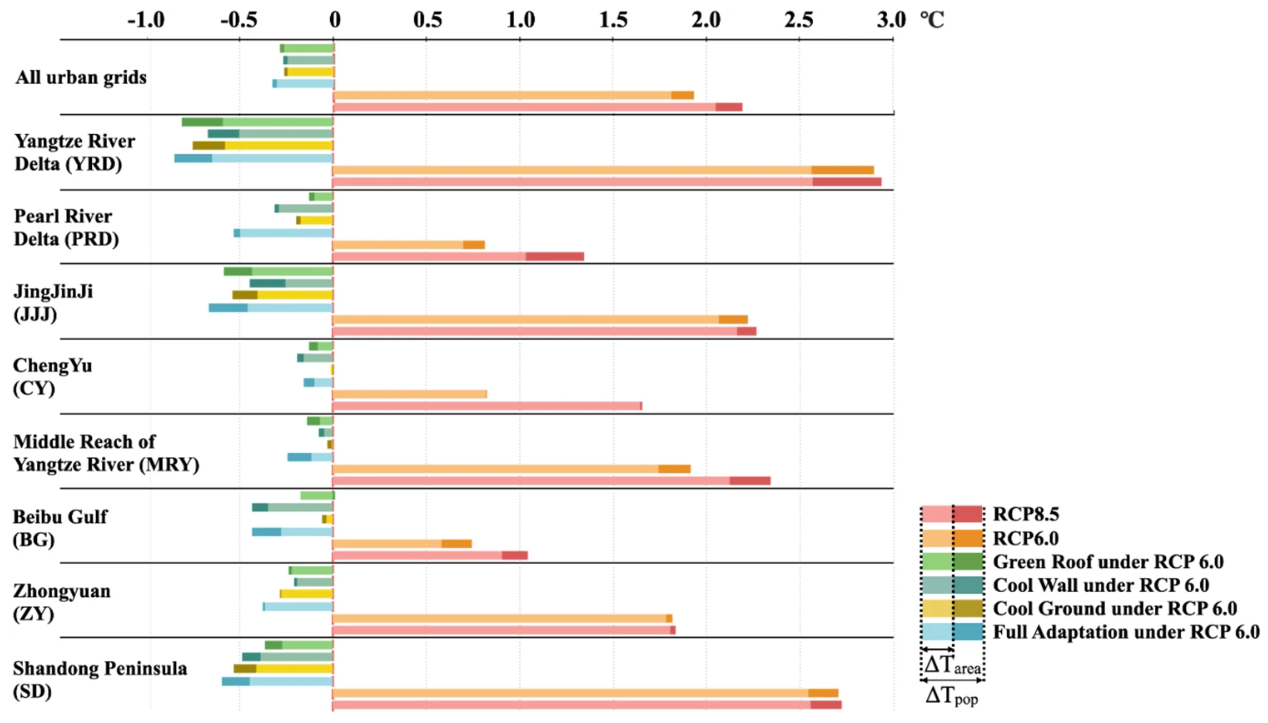

Extreme heat events could become more intense and frequent both locally and globally, increasing the risk of harm to health and global economies, according to a new study that includes research from the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health.

This new research suggests that the burden of heat-induced labor loss would be unevenly distributed among employment industries, creating environmental justice concerns. These impacts could be significantly reduced with careful planning and urban adaptation strategies that include the adoption of things like green roofs and cool walls.

The new study, published today in Nature Communications, investigates the spatial patterns of climate change risks through 2050 among urban areas and also discusses adaptation strategies to mitigate inequity. The authors combined hourly high-resolution heat stress data together with exposure-response functions between heat exposure and labor productivity to examine this inequality.

These high-resolution heat stress data were dynamically downscaled from two different global climate scenarios into a finer scale through a state-of-the-art regional climate model coupled with an urban canopy model.